The Global Atmospheric Circulation on Aquaplanet

The climate system in real world is often complicated and involves many coupled variables. To understand the coupling between the ocean and the atmosphere and the role each played in the whole circulation, an aquaplanet model could be considered as a simplified situation. An aquaplanet in simulation would be a planet with the same solar constant, planetary radius and tilt of axis as the Earth but with no continent and only ocean left on the planet.

The top of the aquaplanet atmosphere would have exactly the same solar radiation condition as the real Earth, as the change on the planet surface would have no impact at this height and no other conditions were different at the top of atmosphere.

As the solar radiation penetrates through the atmosphere, some differences would ap- pear. According to references [1], open ocean has albedo around 0.06, which is much lower than most types of land surface albedo usually varying from 0.1 to 0.4. The planetary surface albedo would decrease due to the disappearance of land. The expansion of ocean would also result in higher water vapour content in the air. More low clouds are formed due to condensation of increased water vapour. The increased reflectivity to incoming solar radiation caused by low cloud formation acts oppositely to the change in surface albedo. The overall change in reflectivity on incoming shortwave radiation is therefore balanced and negligible.

Longwave radiation is emitted by the planet to space. As water vapour content in- creased in the atmosphere, it can be imagined that the greenhouse effect is also enhanced, leading to a warming up of troposphere. Stratosphere contains much less water and is less affected by change in water vapour content. There is even less or almost no change in atmosphere higher above stratosphere.

Overall, the planetary response to shortwave radiation has no significant change and absorption to longwave radiation increases in the low atmosphere. There would be no fundamental change in the global distribution of the solar radiation apart from a global warming-up near the surface. The poleward decreasing pattern of temperature still exists due to the difference of maximum solar zenith angle at different latitudes. This meridional temperature gradient, similar to the one on real Earth, is in balance with a zonal structure of wind belt, also similar to the Earth wind belt. Surface wind is easterlies in the tropics and westerlies in the midlatitude. The change in surface wind speed is not significant, as the impact from shallower temperature gradient is counterbalanced by a reduction in surface friction after removing all land [2].

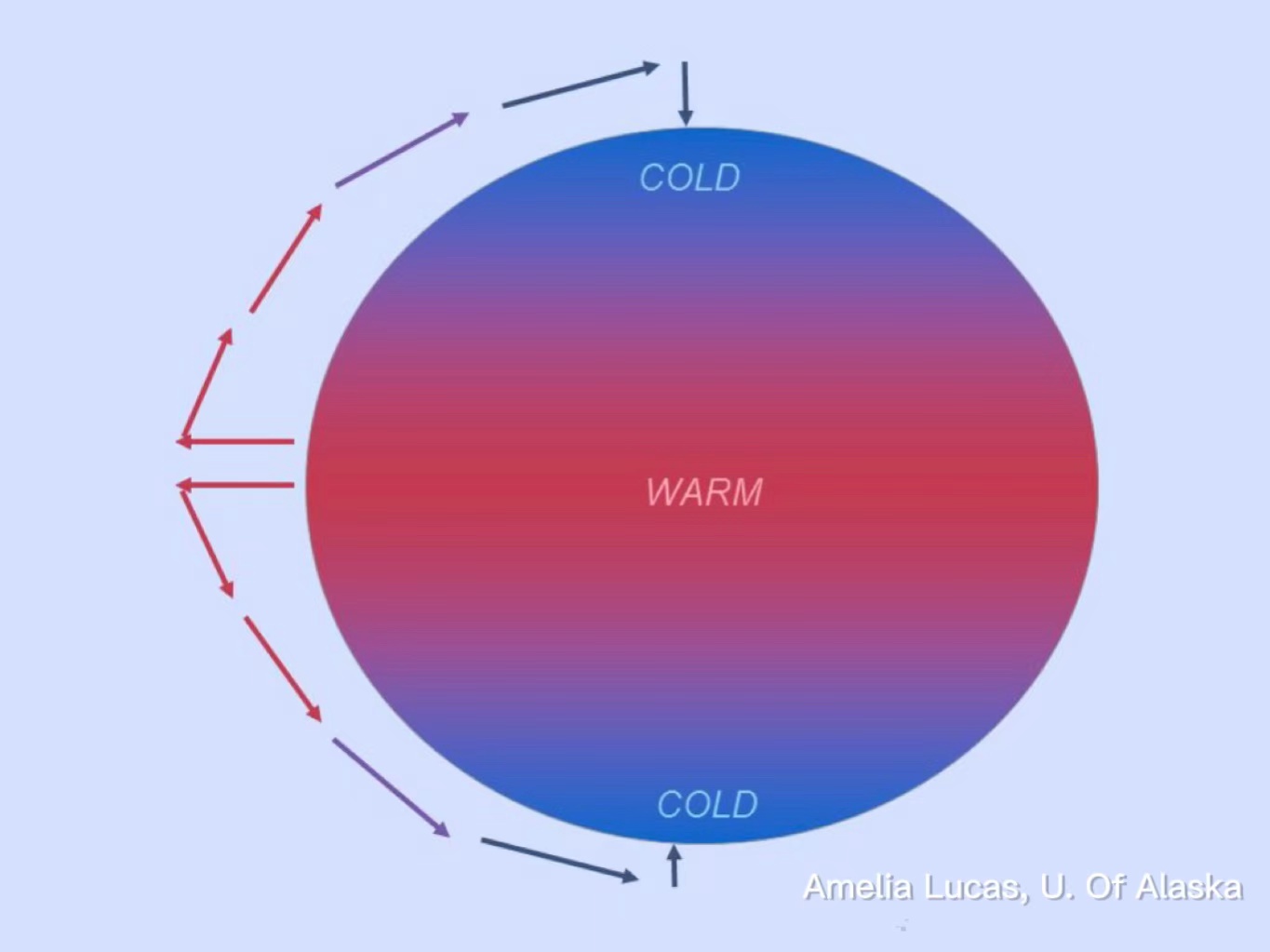

Warm air heats up in the tropics and rises up, transporting heat towards both poles. The poleward wind circulation at high altitude breaks down at a mid-latitude just like on the Earth as the primary planetary setups remain the same. However, water has higher capacity in heat transport and replacing the terrestrial part by ocean means a large increase in heat transport ability. Ocean transports heat globally and acts as a huge heat buffer that mitigates seasonal temperature variation. The meridional temperature gradient is now shallower due to more evenly distributed heat resulted from the increased volume of ocean. Hadley cell is intensified in tropics and the boundary is expanded to higher latitude.

Aquaplanet possesses strong zonal symmetry since the ocean and atmosphere cir- culation have no land or topography barrier. Meridional temperature gradient is also shallower. Since jet stream is partially the result of horizontal temperature difference, the strength of jet stream is weakened. Under a global warming, subtropical jet streams at midlatitude show a poleward shifting, but its general character remained unchanged. At higher up in the stratosphere, Brewer-Dobson Circulation has increased in strength [3].

As the ocean circulating predominantly zonally without land barrier, there is no Sver- drup balance. The Eulerian mean flow and the eddies at mid and high latitudes offset the impact from each other, leading to a much more weakened overturning circulation. Heat transport by ocean to polar regions above 55° largely decreases, causing the temperature at poles dropping to around −15°C. Large amount of sea ice is formed and is estimated to expand to 60° [4]. The polar circulation has great dependance on the polar sea ice condition. With a large area covered by sea ice, polar easterlies almost extinct and the air becomes very dry [5].

Moreover, due to the disappearance of east-west variation in temperature and the zonal symmetry in climate, ENSO phenomenon no longer exists [5].

In conclusion, the general atmospheric circulation on an aquaplanet with no continent has high similarity to that on the Earth. The global meridional heat transport remains high level of constancy, which is mostly determined by parameters like planetary albedo, radius, obliquity and solar constant. Hadley Cell and Ferrel Cell appear no significant change in pattern but slight range shift and strength variation. According to literature [4], the resulting surface temperature at tropics is around 28°C and −15°C at poles. From equator to around 55°, the temperature gradient gets shallower, the mean temperature is higher and the general atmospheric circulation pattern shows no big difference than on the real Earth. However, at higher latitude beyond 55°, due to the lack of oceanic heat transport, large area of sea ice generates significant impacts. Temperature abruptly drops to around −15°C and the polar easterlies disappear.

References

[1] National Snow and Ice Data Center. Thermodynamics:albedo, 2020.

[2] Robin S. Smith, Clotilde Dubois, and Jochem Marotzke. Global climate and ocean circulation on an aquaplanet ocean–atmosphere general circulation model. Journal of Climate, 19(18):4719–4737, 2006.

[3] R. Alan Plumb Gang Chen and Jian Lu. Sensitivities of zonal mean atmospheric circulation to sst warming in an aqua-planet model. Geophysical Research Letters, 37, 2010.

[4] Daniel Enderton and John Marshall. Explorations of atmosphere–ocean–ice climates on an aquaplanet and their meridional energy transports. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 66(6):1593–1611, 2009.

[5] John Marshall, David Ferreira, J-M. Campin, and Daniel Enderton. Mean climate and variability of the atmosphere and ocean on an aquaplanet. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 64(12):4270–4286, 2007.