Ice Cores: Noble Gases as Past Ocean Temperature Proxies

This essay is based on my master thesis and published at Geophysical Research Letters. Please click ResearchGate link here for full text of both.

Ice Cores: Time Capsules for Paleoclimate

A few meters beneath the Antarctic surface, snow from past winters is still recognizable as snow. Go deeper, and that same snow becomes something stranger: a slowly compacting archive that traps tiny samples of the ancient atmosphere. Those trapped air bubbles—sealed away for tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of years—are one of the most direct ways we can measure what the atmosphere was like long before instruments existed.

This is why ice cores are often seen as “time capsules.” They contain more than ice: they preserve aerosols, dust, volcanic signals, and gases such as CO₂, CH₄, and N₂O. And because the layers build up year by year, many ice cores behave like a climate library arranged in chronological order (so-called continuous cores).

The use of ice cores in paleoclimate studies was first proposed in the 1950s by Willi Dansgaard [1]. Today, the longest widely used continuous Antarctic ice-core records reach back roughly 800,000 years. Scientists are now pushing beyond that—toward 1.5 million years—to better understand how Earth’s glacial cycles worked before they shifted into the rhythm we’re familiar with.

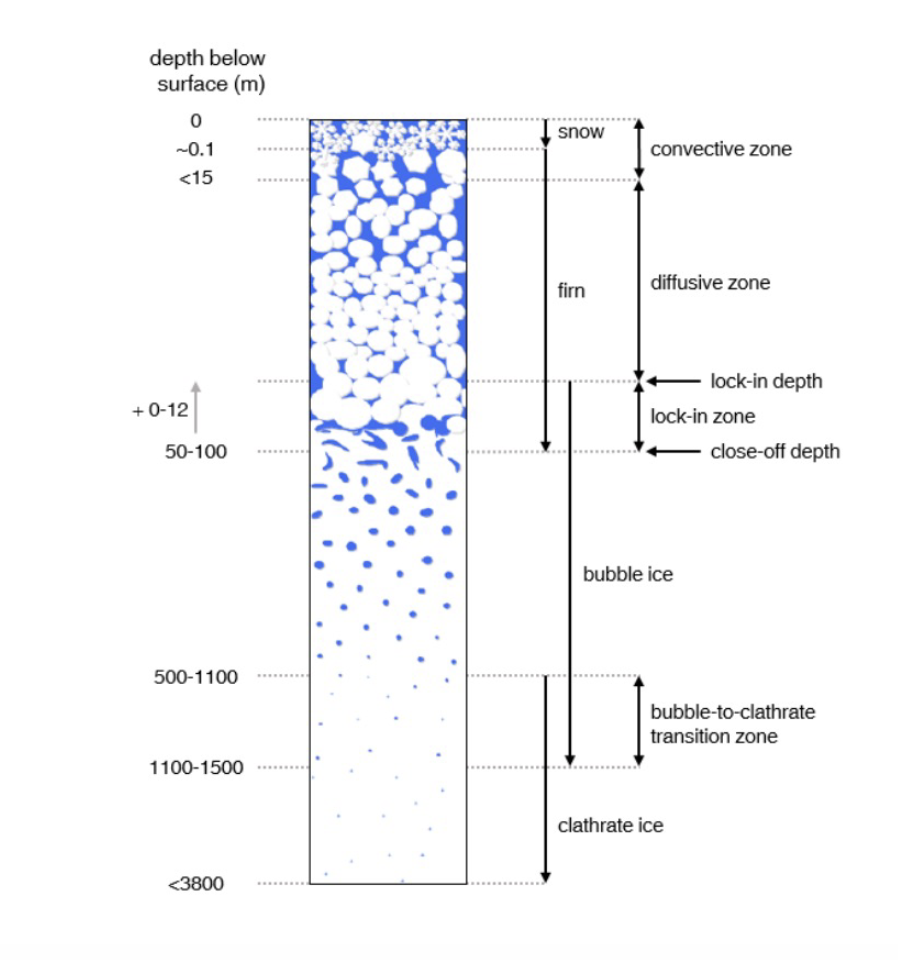

Fig.1 Schematics of the fim column [2]. In polar regions, snowfall accumulates and compresses under its own weight. The upper tens of meters are still porous, like a stiff sponge. This porous zone is the firn layer, typically on the order of 50–100 m thick [3]. Air can move through firn, meaning the ice at that depth is not yet “sealed off” from the atmosphere. Eventually, the pores close and air becomes trapped as bubbles at the bubble close-off depth. It can take up to 3 kyr (1 kyr = 1000 years) for air to be fully isolated [1].

Mean Ocean Temperature Reconstruction

The global mean ocean temperature (MOT) is an important measure for the state of Earth climate: as the ocean stores over 90% the excess heat in the climate system, MOT reflects the global energy balance status. Reconstructing MOT is hard, though. Many proxies have been proposed for the paleoclimatic reconstruction of the oceantemperature, for instance, the ratio of magnesium to calcium in benthic foraminiferal species [4], heavy oxygen isotope content of fossils or carbonaterocks, and Sr to Ca ratio in the corals. But they tend to reflect local or regional conditions, and they can be influenced by biology or chemistry processes that are not fully understood yet.

That’s where noble gases become attractive: their behaviour is dominated by physics [5].

Noble Gas Proxies

Noble gases (Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe) are chemically inert under Earth-surface conditions. They don’t get consumed by ecosystems, and they aren’t produced or destroyed by the common chemical reactions that shape many other climate tracers. Over the timescales relevant for glacial cycles, their total amount in the Earth system is close to conserved:

Itot = Iatm + Iocn

where Iatm and Iocn are the atmospheric and oceanic inventories. This conservation makes noble gases unusually “clean” proxies: the signal is dominated by physics rather than biology or reactive chemistry.

The key idea is solubility. Noble gases dissolve in seawater, and their solubility depends strongly on temperature:

- Warm ocean → lower solubility → more noble gas remains in the atmosphere

- Cold ocean → higher solubility → more noble gas dissolves into the ocean

If the ocean cools, it can “pull” a little more noble gas out of the atmosphere. If it warms, it “releases” some back. These shifts are small, but measurable—especially using ratios such as Kr/N2, Xe/N2, or Ar/N2 in air bubbles trapped in ice cores. Because N2 is abundant and comparatively stable, ratios help reduce certain calibration and measurement artifacts.

Our Contribution: A Slightly Warmer Past?

For a long time, MOT deduced from noble gases is based on the assumption that the saturation rate is 100% in the ocean. This is a good assumption as ocean circulation is slow enough for surface water to get fully saturated before sinking down. However, our simulation results show that the ocean’s noble-gas saturation shifts when the “air–sea exchange machinery” changes: winds can stir and refresh the surface, sea ice can act like a lid that slows exchange, and circulation changes can alter how quickly surface waters and the deep ocean get ventilated. These influences can push in different directions and sometimes partly cancel.

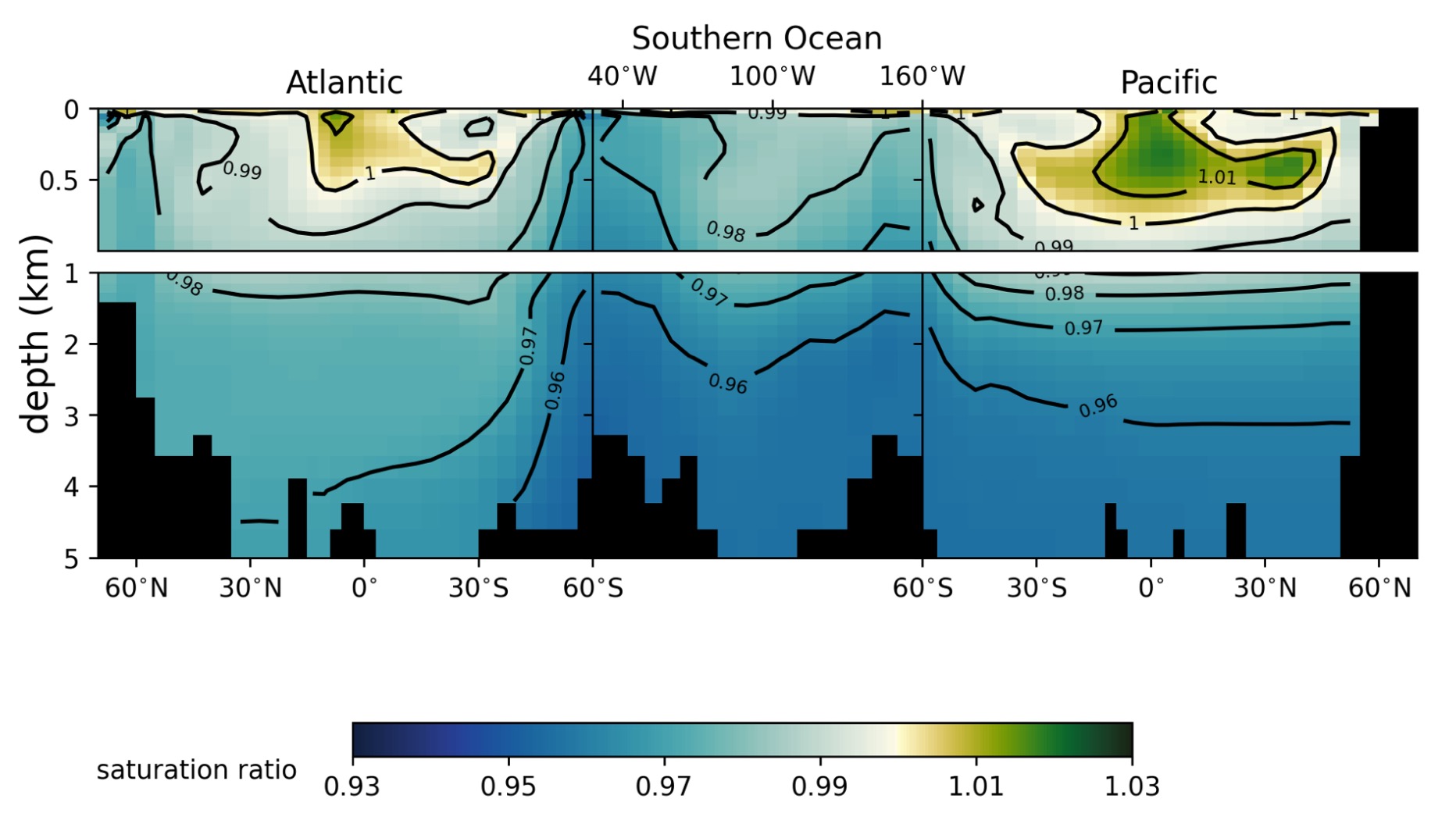

Fig.2 Example plot of Kr saturation distribution in Bern3D simulated ocean during sensitivity tests.

Why does this matter for reconstructing mean ocean temperature (MOT) from ice-core air bubbles? Because the atmospheric Kr/N₂ and Xe/N₂ signals we measure are shaped by both temperature-driven solubility and saturation-driven disequilibrium. Accounting for the modeled saturation effects, we suggest the LGM-to-preindustrial MOT cooling is about −2.1 ± 0.7 °C, roughly 0.5 °C warmer than many earlier noble-gas-based estimates—still a big glacial cooling, just not quite as extreme once the ocean’s changing ability to exchange gases is properly included.

References

[1] Winckler, G. and Severinghaus, J. (2013). Noble Gases in Ice Cores: Indicators of theEarth’s Climate History, pages 33–53.

[2] Schwander, J. (1996). Gas Diffusion in Firn. In: Wolff, E.W., Bales, R.C. (eds) Chemical Exchange Between the Atmosphere and Polar Snow. NATO ASI Series, vol 43. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-61171-1_22

[3] Schwander, J., T. Sowers, J.-M. Barnola, T. Blunier, A. Fuchs, and B. Malaizé (1997), Age scale of the air in the summit ice: Implication for glacial-interglacial temperature change, J. Geophys. Res., 102(D16), 19483–19493, doi:10.1029/97JD01309.

[4] Bryan, S. P., and T. M. Marchitto (2008), Mg/Ca–temperature proxy in benthic foraminifera: New calibrations from the Florida Straits and a hypothesis regarding Mg/Li, Paleoceanography, 23, PA2220, doi:10.1029/2007PA001553.

[5] Ritz, S. P., Stocker, T. F., and Severinghaus, J. P. Noble gases as proxies of mean ocean temperature: sensitivity studies using a climate model of reduced complex- ity. Quaternary Science Reviews, 30(25):3728–3741, 2011. ISSN 0277-3791. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.09.021.